Back in 1978 Stephen King was an author with a couple of bestsellers under his belt and things were seemingly getting bigger with each book. So for his fifth act, he chose to wrote about the Patty Hearst kidnapping. That didn’t pan out, so after a while he switched gears and started writing The Stand.

Back in 1978 Stephen King was an author with a couple of bestsellers under his belt and things were seemingly getting bigger with each book. So for his fifth act, he chose to wrote about the Patty Hearst kidnapping. That didn’t pan out, so after a while he switched gears and started writing The Stand.

Things got bigger alright, with the original manuscript clocking in at 1200 pages. The publishers requested that a third should be culled, and so it was. Until 1990, when the full uncut (and slightly updated) version saw the light of day.

The Stand is a good vs. evil epic against an apocalyptic background, with America and the world succumbing to a deadly man-made virus nicknamed Captain Trips. However, some people are immune, and begin having strange dreams, either of a black woman or a dark man (they are of no relation to each other). Following their dreams, the survivors traverse the ravaged landscape and make their way to Mother Abagail the ancient black woman and establish a Christian colony of survivors called the Free Zone in Boulder, Colorado. Meanwhile the dark man, Randall Flagg, establishes another colony of survivors in Las Vegas following another set of values. Inevitably confrontations ensue between the two factions. It’s a simple story but it takes a whole lot of pages to tell it.

The length is initially a strength, with King languidly introducing the main players, beginning with Stu from East Texas, who is there at the beginning when the virus hits and is the white hat of the story. Larry the musician has a hit song just as the apocalypse hits, while Nick the deaf-mute drifter gives the looming apocalypse an extra dimension due to his inability to hear or speak. Nick eventually pairs up with Tom the mentally handicapped man who cannot read (oh the irony) and for whom everything spells M-O-O-N. Fran the pregnant girl is the only survivor of her town in addition to Harold the fat kid, who has an unrequited crush on her. Lloyd the convict gets a job as Randall Flagg’s lieutenant and Nadine becomes Flagg’s secret bride. And so on, the first half of the novel recounts their lives before and immediately after the end of the world as they knew it, and how they eventually find their places in the new world. King takes his time to set his pieces on the board, pays minute attention to some of them, giving them small adventures that do not really progress the plot, but contribute to its solid foundation. The first half is all about a build-up to something epic.

Unfortunately, that’s where The Stand collapses. The second half of The Stand is dull as dishwater. It doesn’t help that most of it consists of meetings and other bureaucratic endeavours of the new settlement. If something breaks the tedium, it happens suddenly and without reason, like a bomb that suddenly goes off. King has gone on record that the bomb was a way to get the characters moving again, but similar things happen again and again in the second half, culminating in the detonation of a nuclear bomb by the infamous hand of god. It’s as if King literally lost the plot in the second half and made something up on the fly, slouching towards the end because he’d made it that far, there was a book to deliver and that Patty Hearst idea wasn’t going to resurrect itself.

There are problems with some of the characters as well. Stu as the leading man is another Ben Mears of ‘Salem’s Lot fame, a bland white male hero, annoying to a fault because there is barely anything there. Fran the pregnant girl is the leading lady, who comes off as a grounded figure in the beginning but then degenerates into a shrill new mother archetype. These two milquetoast characters are going to be the Adam and Eve of the new world? Please. Mother Abagail the ancient magical black woman is problematic to say the least, and that’s all I’m going to say about her. Glen the professor has Kojak the smart dog and Ralph the man with the pick-up has a pick-up. Some of the characters, however, do grow up in the course of the novel, most importantly the cowardly Larry who does become something of a righteous man, as per the lyrics of his song. The tragedy of Harold the incel is also noteworthy. He tries to become a better man and even does, but is eventually undone by his inability to let go of the mocking rejection by Fran. And Randall Flagg as the cool, calculating counterpart to the goody-good God-worshipping Mother Abagail lights up every scene he’s in.

However, the biggest character in The Stand is God. He’s pushing Mother Abagail to make a stand, he’s assembling the heroes, and it’s literally his hand that ends the book. The world after the superflu is divided into two camps of good and evil, black and white, with no shades in between. There are no gray areas in The Stand, no characters that would just go thanks but no thanks, we’re good, when nutcases come calling them to join their silly quests. Whatever sense of realism King’s prose had accumulated in his career by this point goes out the window and is replaced by simplistic superstitions. And it’s all the more painful because there’s nothing original or inventive in these choices. Going biblical may help make your book more epic just because the Bible is the original epic, but it feels lazy and uninspired.

However, the biggest character in The Stand is God. He’s pushing Mother Abagail to make a stand, he’s assembling the heroes, and it’s literally his hand that ends the book. The world after the superflu is divided into two camps of good and evil, black and white, with no shades in between. There are no gray areas in The Stand, no characters that would just go thanks but no thanks, we’re good, when nutcases come calling them to join their silly quests. Whatever sense of realism King’s prose had accumulated in his career by this point goes out the window and is replaced by simplistic superstitions. And it’s all the more painful because there’s nothing original or inventive in these choices. Going biblical may help make your book more epic just because the Bible is the original epic, but it feels lazy and uninspired.

The uncut version of 1990 returns the previously cut third back into the fold, and also updates some of the dates and pop culture references to account for the 12 year gap. While the longer version gives the novel more breathing room, the changes are surprisingly minute. Anything that didn’t work in the original edition still doesn’t work. It’s just more. King’s notoriety as the writer of long books was probably spawned here, even if his following books were quite condensed and effective and the bloat would only return much later. Of the previous books, The Stand perhaps best resembles ‘Salem’s Lot with its large cast, but whereas the vampire saga was set in a single town, The Stand spreads it out to all of North America. The contrast is even more striking in comparison to The Shining, which was confined into one hotel. A boundless sandbox isn’t perhaps the best match for King, or for horror in general.

There’s a lot of good in The Stand. All of the first half is excellent, with the characters journeying through the apocalypse seeking safety. The dying world is perfectly captured, with survivors of the superflu still facing many other deadly situations, not to mention mental problems. There are excellent small nuggets, such as the chapter where King rapidly goes through a series of quick snapshots of ordinary people suffering a variety of fates. But once the main cast arrive in Colorado and make their stand, it all stumbles into a standstill. One of the points of this re-read is to remind myself what the books were actually like, and everything in the first half was just as good as I remembered it from several decades ago. But I had no recollection of the second half at all, other than from the two TV miniseries, and getting through it felt like a boring chore, not an enjoyment. There’s no denying that The Stand is a classic story of an apocalypse, and some of it is great, but half of it isn’t.

** (2/5)

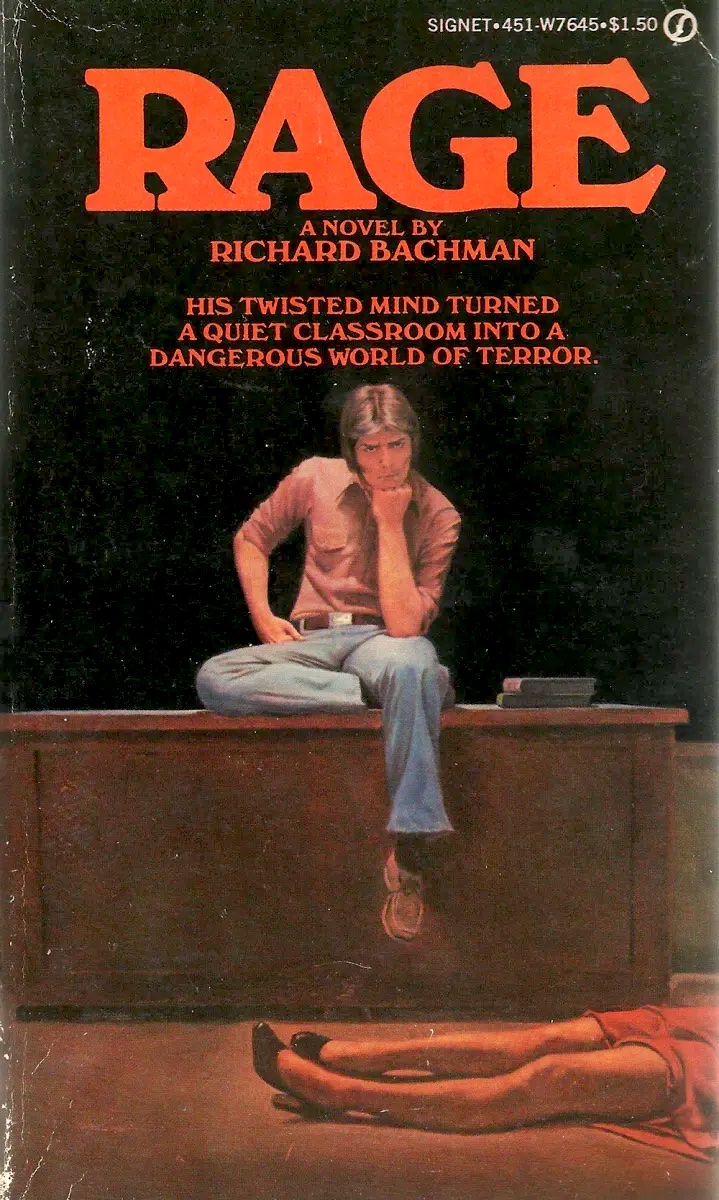

This was book 6 in my Stephen King re-read. Next up: The Long Walk by Richard Bachman

The Dark is a 1980 horror novel by James Herbert, where a sentient darkness is making people violently insane. By 1980 Herbert was starting to turn away from the fast-paced style of The Rats and The Fog that made his career. His following works would display a more experienced writer, and while The Dark is a step out of the past, it also still contains all those trademark vignettes where a character is introduced only to be killed a paragraph or two later.

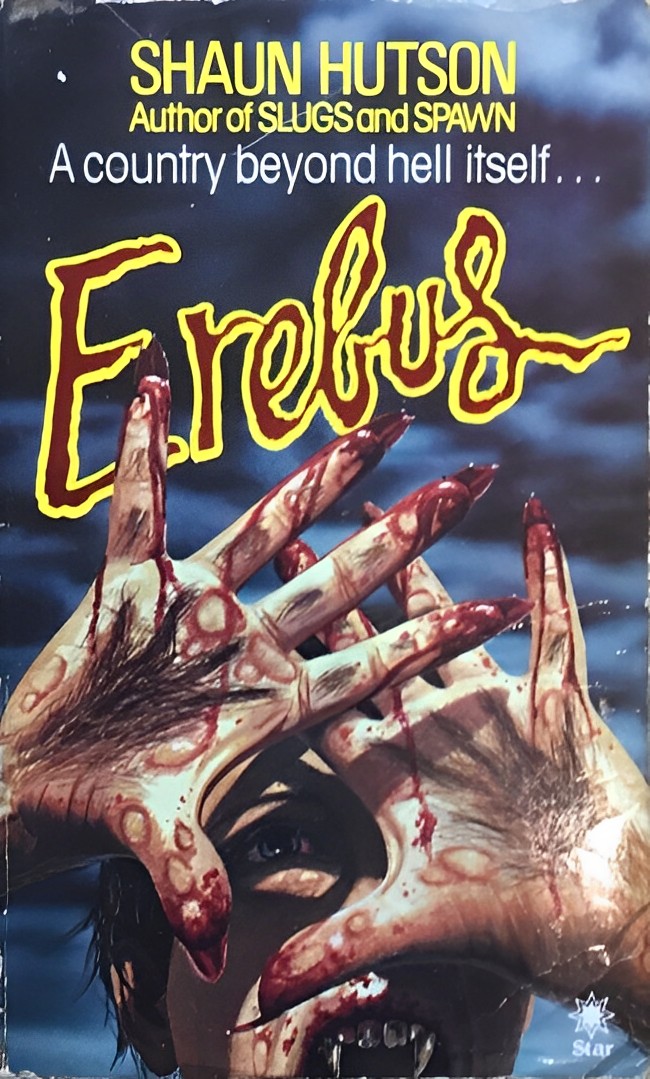

The Dark is a 1980 horror novel by James Herbert, where a sentient darkness is making people violently insane. By 1980 Herbert was starting to turn away from the fast-paced style of The Rats and The Fog that made his career. His following works would display a more experienced writer, and while The Dark is a step out of the past, it also still contains all those trademark vignettes where a character is introduced only to be killed a paragraph or two later.  Erebus is a 1984 horror novel by Shaun Hutson, set in the bucolic English countryside. The green and pleasant land is soon dripping with blood as a mare kills its own newborn foal, while at the abattoir it’s the bulls that get to do the slaughtering for a change. Unsurprisingly, the people who have eaten the meat of the tainted animals also start exhibiting bestial behaviour, sporting new canine teeth, their skin turning pale, hair growing from their palms… which I think traditionally means that they masturbate excessively? Anyway, it’s up to Jo the journalist and Tyler the farmer to solve the case and have a couple of explicit sex scenes, while dodging zombie vampires and a hitman, among other threats. Heads will explode, spines will be severed.

Erebus is a 1984 horror novel by Shaun Hutson, set in the bucolic English countryside. The green and pleasant land is soon dripping with blood as a mare kills its own newborn foal, while at the abattoir it’s the bulls that get to do the slaughtering for a change. Unsurprisingly, the people who have eaten the meat of the tainted animals also start exhibiting bestial behaviour, sporting new canine teeth, their skin turning pale, hair growing from their palms… which I think traditionally means that they masturbate excessively? Anyway, it’s up to Jo the journalist and Tyler the farmer to solve the case and have a couple of explicit sex scenes, while dodging zombie vampires and a hitman, among other threats. Heads will explode, spines will be severed.

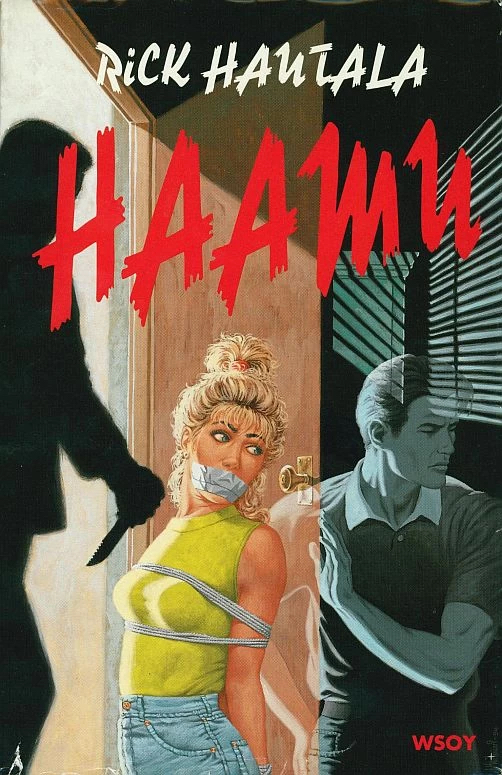

Sarah is a teenager with a guardian angel, a personal ghost whose modus operandi is to kill anyone who displeases Sarah. Having accidentally gotten her cat and her little brother killed this way, Sarah is understandably beginning to feel some remorse. Then her mother gets brutally raped and killed by a stranger, which Sarah witnesses from a distance. In this situation the ghost, Tully, proves mostly useless, although he does later dispatch her new (pregnant) stepmother, establishing that he only attacks those who are easy prey.

Sarah is a teenager with a guardian angel, a personal ghost whose modus operandi is to kill anyone who displeases Sarah. Having accidentally gotten her cat and her little brother killed this way, Sarah is understandably beginning to feel some remorse. Then her mother gets brutally raped and killed by a stranger, which Sarah witnesses from a distance. In this situation the ghost, Tully, proves mostly useless, although he does later dispatch her new (pregnant) stepmother, establishing that he only attacks those who are easy prey.

Chandal and Justin are a young couple living in Manhattan when they receive an irresistible offer to move into one of New York’s elegant and desirable apartment buildings. Grabbing the deal of a lifetime they move in, but soon Chandal begins seeing ghosts while Justin becomes increasingly strange and secretive. Turns out the two elderly sisters who own the brownstone are actually demon-worshipping cultists who want the couple for their own nefarious ends.

Chandal and Justin are a young couple living in Manhattan when they receive an irresistible offer to move into one of New York’s elegant and desirable apartment buildings. Grabbing the deal of a lifetime they move in, but soon Chandal begins seeing ghosts while Justin becomes increasingly strange and secretive. Turns out the two elderly sisters who own the brownstone are actually demon-worshipping cultists who want the couple for their own nefarious ends.

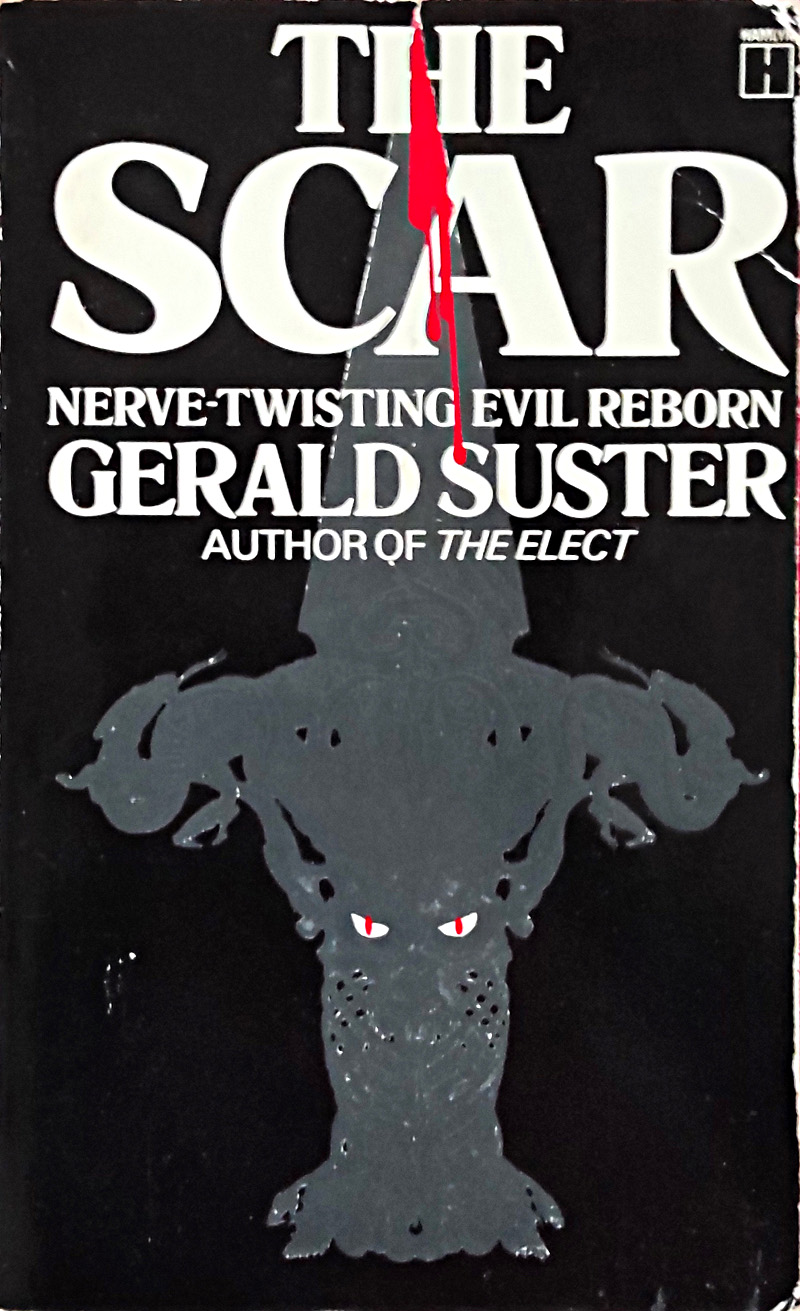

Helen is the new raven-haired student at a prestigious private college for rich kids and everyone has the hots for her. Soon she attends a Satanic ritual the other students are having for, you know, shits and giggles. The ritual fails, Satan doesn’t appear, but Helen suddenly goes berserk and tries to bite a fellow student. She soon recovers, but begins exhibiting strange behaviour, being even more promiscious than before. Nothing like an occult ritual to make you lust for sex. Later, one by one, she seduces and copulates with every man who was present at the ritual, all of whom end up dead in a variety of ways soon after the deed is done. She also makes fast friends with a solitary crow and a horny on-the-dole voyeur. Or familiars, as one might call such bestial servants. She also has a small scar below her breast, which gives the novel its title.

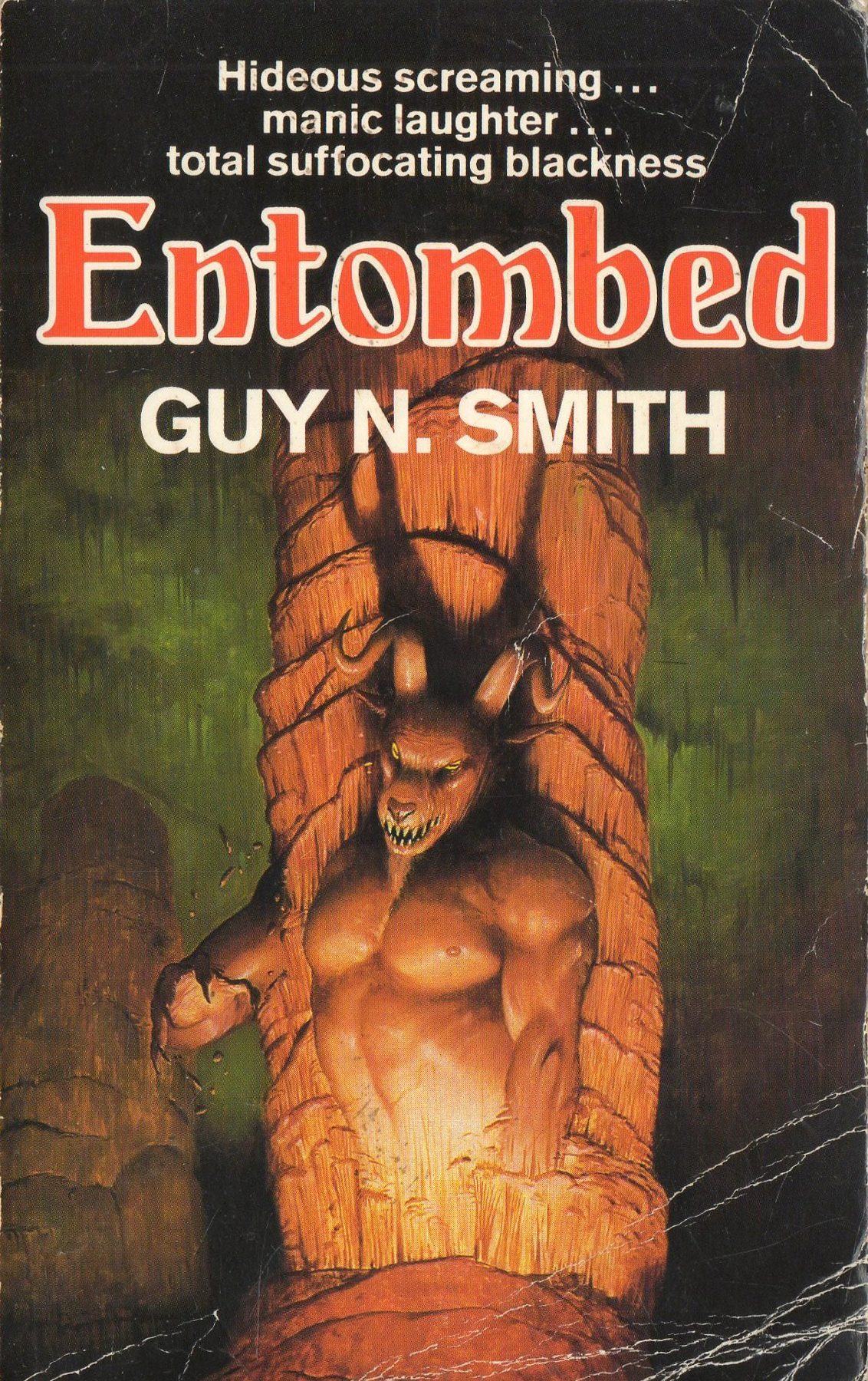

Helen is the new raven-haired student at a prestigious private college for rich kids and everyone has the hots for her. Soon she attends a Satanic ritual the other students are having for, you know, shits and giggles. The ritual fails, Satan doesn’t appear, but Helen suddenly goes berserk and tries to bite a fellow student. She soon recovers, but begins exhibiting strange behaviour, being even more promiscious than before. Nothing like an occult ritual to make you lust for sex. Later, one by one, she seduces and copulates with every man who was present at the ritual, all of whom end up dead in a variety of ways soon after the deed is done. She also makes fast friends with a solitary crow and a horny on-the-dole voyeur. Or familiars, as one might call such bestial servants. She also has a small scar below her breast, which gives the novel its title.  Simon the Exorcist has failed at his job, his faith has deserted him, and his wife has left him for someone wealthier and taken the kids, who now call their mom’s new man their “daddy”. It’s also raining, because this is Britain. A short trip to rural Wales seems just the ticket to get his life on track.

Simon the Exorcist has failed at his job, his faith has deserted him, and his wife has left him for someone wealthier and taken the kids, who now call their mom’s new man their “daddy”. It’s also raining, because this is Britain. A short trip to rural Wales seems just the ticket to get his life on track.